We were seven all, two too many spilling out the sides of the five-seater — Three windows open, one—behind—broken, hairline fractures spilling down from a jagged corner — I twisted toward an unbroken window, the leather of the car seat clinging painfully to the undersides of my thighs tender and blistering as I leaned backwards, away from the mass of sunburnt limbs in the backseat. Eyes stinging from Etesian-stirred dust, the crown of my head already sun-lanced and smarting, I watched him: watched the glare-bleached fuzz flittering on the backs of fingers curled around the peeling steering wheel, the tremor in the ring finger and pinkie, a proactive, past-perfect souvenir from his father’s side travelling in a lazy arc, up-and-down-and-sideways with the wheel in tandem with the wheels around switchback after switchback, pins in the mountain’s thistle-bush hair — Prophetic perfect: I died. I will die—I have not yet; but it was imminent. My every surrounding (the cicadas’ screaming; the Coke bottle growing warm, sweating between my thighs; the salt crystallising on my lip) was converging into a hot static, breathing down my neck, curling around my throat, down my oesophagus, asphyxiation from the inside out—every breath a bruising grip.

My cheek burned white-hot. He held a shred of the broken window below my eye, looking sidelong at me, blindly rounding a corner, left hand still tremoring around the wheel — I could see, beyond the glass threatening to pierce through my cornea into the jelly flesh underneath, the scar short and thick across his forearm. He cut himself with my Swiss army knife once: standing in my room, sleeve drawn up, he dragged it across his arm once, twice: the second drew blood — He stood before me, palm up, eight years old not saying a word, looking up through sharp, straight lashes, staring, devouring, bleeding onto the floor, droplets creeping between tiles to coagulate into mortar, thick and brown — I stood and cried — He told my mother I’d slashed him — I didn’t see him for a month, but when I did, he smiled, silent, and showed me the scar.

He removed the sun-hot shard from my cheek — I looked at him and he said nothing — I fell asleep in a tunnel near Corinth and awoke on Spartan back roads: spare, ugly — The bridge the Nazis crossed when my grandfather was a boy — The riverbed cracked and dry — I had dreamt of a boar like the ones who run across country roads at night across artificial sunbeams of machines come to mow them down, inevitably — In the dream I was attacked by one risen from its streetside grave to chase me down until I caught hold of it, wrapped my arms around its stomach, and it began to shrink, ageing in reverse until I had a baby boar pinned between my index and thumb — I pressed and pressed and its eyes—dark capers of fear—bulged but it made no sound and I awoke with sweat in my eyes and a dull pain in my neck.

Another hour trailed in the truck’s wake and we came to the village at the base of the mountain, white-red rottenstone ridges dotted with olive trees obscuring the faint line of the Laconian Gulf on the horizon. Our village; the others were city-boys through and through, Horace-Mann-School nicotine-pouch-raised Penn-bound Wall-Street-wannabes with faintly Greek botoxed mothers and cocaine-gacked WASP-stinger fathers who left them to muck about with the country dirt during their annual yachting pilgrimage to Porto Cheli — We—me and him—were nouveau-riche, no Nantucket colonial mini-mansion, Balkan upstarts gone East Coast two generations back — Shipping magnates doing the dirty work, hauling ass across the Atlantic, and one generation later his father the prodigal son back from Wharton to build casino resorts and milk-and-honey condos (good news for nobody, they all joked) — Gotta make up for lost time — We still returned, then, to the village of our grandfathers, and the others marveled at the rusting pickup truck he salvaged from the lot behind his house and bought plastic-bottled white wine for one-euro-fifty and walked about in plastic shoes for four days of pretend-poverty before the drive back to Athens, throwing drained bottle-husks into passing truck-beds.

We turned into the driveway, the house a child’s lopsided terracotta creation and next to it an earth-scar, the foundation for its replacement—one can’t play at poor forever—a soon-to-be chalky beacon watching over the orange groves — On the left, a chain-link fence warped by a twisting grapevine, sugar-crazed wasps hovering over the rotting fruit — On the right, a wall rising stone by stone, handmade by an Italian luxury artisan because his father refused to live like a dog if forced—by eusebeia; by the nagging aunts who half-raised him—to pay the village an annual visit — Out of the car and into the house smaller than my SoHo living room — A kitchen with decade-old cans of Alfa lining the windowsill — A bedroom turned labyrinth, scattered: one bed, two cots, a shapeless mat on the floor (sharing a mat was a great adventure for boys who had never lent more than a lighter) a peephole window in the wall overlooking the cistern.

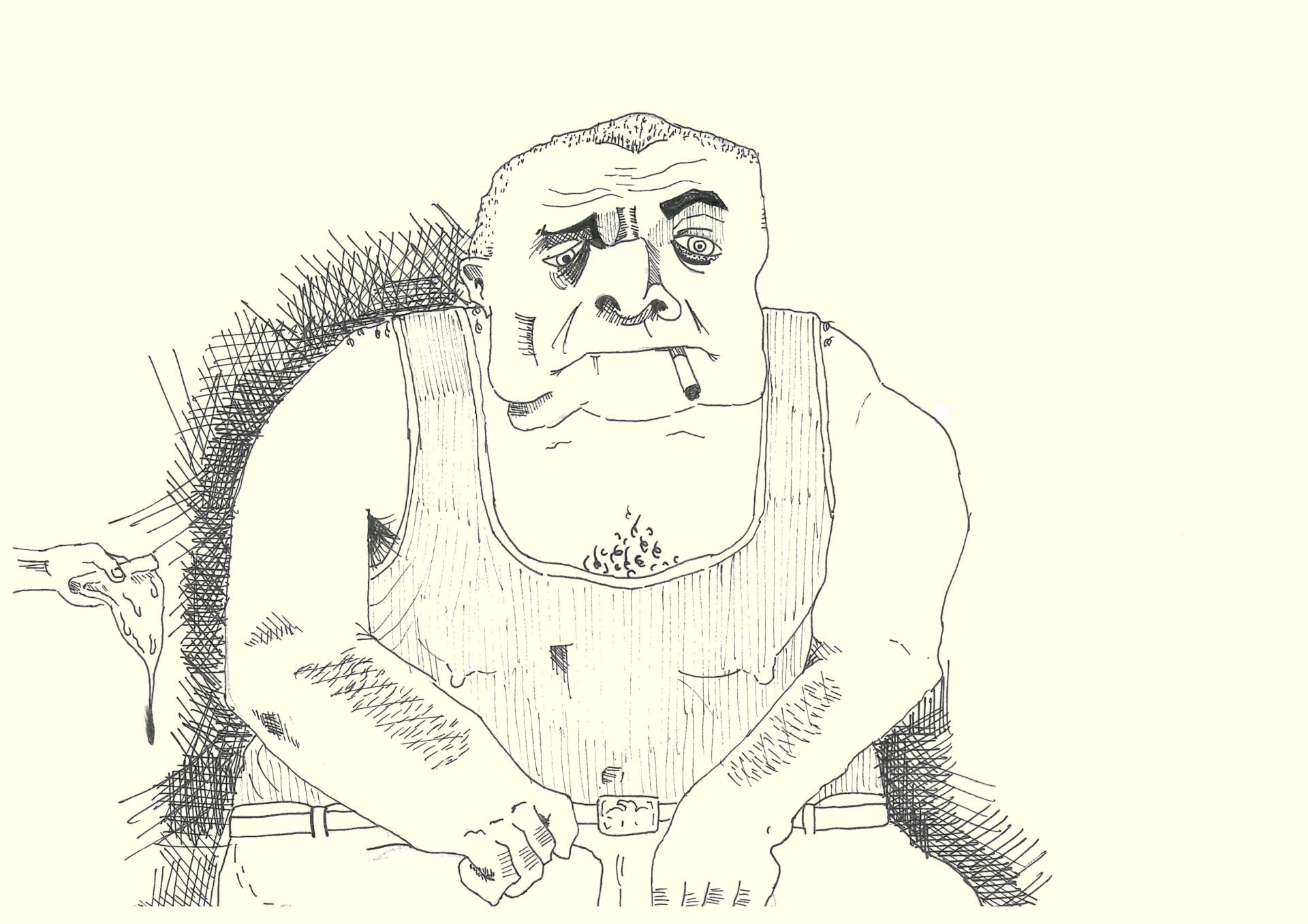

The village was empty as we walked toward the square. We passed a lone horse grazing unbridled behind a dumpster — A tabby on a discarded mattress, weakly pawing at branches of spiny spurge poking through — One of the others—a spindly faux-blonde who moved as though he had revolving joints—drifted across the street, reaching through open car windows in search of a stray cigarette pack and returned foul-smelling and successful, bearing gifts for the group — I imagined our lungs all mildewing beneath premature ribs. The cigarettes were stale and we coughed and coughed and coughed. Into the bar on the village square with the burgundy seats and the soft-serve machine — Chocolate, Vanilla, Swirl, but they all tasted the same. Then, there: in a corner, half-covered by a curling fringe, a face unseen since the summer before — She sat beside her father, a fat sun-reddened man in a sweat-stained wife beater who frowned, watching her stare across the room — At him — Standing beside me — One of the others joked there’s your competition — Another: beauty and the beast — He said low-hanging fruit and they all laughed like he was the fucking messiah — He walked to her as her father half-shuffled to a barstool — And we took our seats, obedient — The bar only served pizza that time of night — Flimsy — I suffered one bite and abandoned ship — Watching your figure? — Squawking laughter — Jesus Christ.

Later I laid in bed (I’d won the race back to the house, watched them tumble down the drive and howl at the roaming dogs in the street from behind the iron-woven safety of the gate) and tried not to twitch, my mind seven hours behind my body, discarded somewhere in the JFK parking lot. I had heard, from someone I no longer remembered, that laying corpselike for twenty minutes could transport you into a state of lucid dreaming. I imagined myself trembling so quickly that the air around me hummed with energy and I began to rise, first through the ceiling—atoms dodging atoms, impossibly, in perfect harmony, a pas de deux between millions side—stepping each other’s pull — I watched from above as the sun sped in a circle above solar farms and orchards over and over and over again until I heard the rooster cry outside, its mistimed call (dawn was still hours away) wrenching me from my flight —

A mosquito buzzed at the corner of my consciousness — I buried my face under a pillow but threw it off, gasping for air after four hot, suffocating breaths — The cock screeched, spearing me with its irregular calls — One after the other after — I scratched at my scalp — I tried to track the rhythm of the other’s snores with my torturer’s crowing and imagined suffocating us all, turning on the gas and blocking the viewless window, stuffing a salt-saturated beach towel beneath the heavy door (with that handwritten note on the front—there is nothing—to ward off thieves) — Placing my pillow over their faces, one by one — The cock crowed and I missed my mother and bit my fist and feared I would never sleep again.

I awoke damp and sour, sheets hanging off the foot of the bed, grains of sand pressed beneath my cheek and the midmorning sun swallowing the room a reminder to my sleep-starved mind that I had just barely escaped death — She sat cross-legged on a cot in the corner with one of the others, eating Kellogg’s from the box — Everyone else outside with the dogs that pissed all over the floor when I first met them, overexcited, so eager to love — One of the dogs barked and a few cornflakes fell to the floor and the other one sitting beside her stared at her pierced bottom lip (the piercing was rejecting, skin inflamed around the hoop, and I hated that boy for idolising her and the crumbs caught in her crusted lips.)

But she was beautiful — Once, in a hostel room on Elafonisos, eight draped as one on the floor, a mass of sleeping arms and wine-warmed breath—she put her fingers in my mouth — I could see the whites of her eyes, faint spots in night’s purple shadows as she bent over me, forcing thumb then pointer as far as she could reach. Her knuckles scraped against my teeth, drops of her blood dampening my lips; her nails scratched my throat — A buck scraping its antlers against a tree, wearing the bark away to reveal the umber heartwood below, tattered velvet hanging down in bloody strips — One of the others groaned, shifted in sleep — The next day she brought up Freud at the breakfast table, pronouncing oral stage slowly, dragging it up from deep in her throat, looking at him, pressing the ball of her foot between my trembling thighs underneath the tablecloth until my stomach began to turn inwards on itself — The sun’s warmth and the sweat pooling behind my knees and the milk drying along my lip—hateful, all, burning, suffocating me one pore at a time — I went back to sleep that morning, buried beneath bits of driftwood in a fisherman’s shack in the sand as they all swam among the rockfish and urchins — And woke sun-bronzed and half-mad in the car, hot skin fusing with leather, so hungry I felt that I could never stomach another bite of food. But back to the little house with the Kellogg’s and the cots — She watched my waking moment and the other one watched her and I walked out into the kitchen for a carton of warm peach juice (we all accepted that the fridge was broken, but kept it connected—to keep the house a home) and drank two and stepped out by the half-raised wall to watch the dogs at play.

We made the journey North eight all, one too many piled into his car — Three of the others relegated to the truck bed — We drove past the cracked river bed and through mountains of dirt sliced in half to make way for the road — Mountains lingered on the horizon, red or slate or green with summer-fed growth until the next range came to replace them — We argued in a rest-stop parking lot — I spent the next two hours in the back, exposed, watching the coastline ebb and flow — I held my breath, as I always had, when we passed the foetid factory an hour out of Athens and watched the others cough — I sipped, mistakenly, from the coffee cup the others were using as an ashtray and cast it away, heard it explode under the wheel of a passing Fiat. And then we were back in Athens with its dust and sun-worn paint and graffitied clovers—zito Panathinaikos—and occasional Golden Dawn swastika-meanders on overpasses and corners of violated trucks — The dirt-stained car was hidden away in the garage and we boarded the elevator to be carried up and home through the building’s cement entrails.

Hours later, we stood on the roof and threw pistachio shells at the clubgoers staggering out of taxi cabs toward ATMs to pay the fare with money they didn’t have — Listened to the cabbies shout at each other across narrow roads — Watched the Parthenon shine sickly yellow against a moonless sky — Tried to light the grill, restless and hungry at half-past three, but the flames spat up at us, singeing eyebrows — He was bitter, teeth bared: his father had called — Trouble in paradise — A farmer, at the epicentre of a prospective development, holding onto his land — Good news for Nobody, bad news for Somebody — Joking laughs grew jeering; words caught in throats — Resigned — We fell down the sharp marble steps and went to sleep in silence — Save for the occasional engine-scream — And no one woke before two in the afternoon.

The others had gathered by the time I made it to the kitchen—he sat at the head of the table, knees drawn to his chest, adolescent King Arthur at counsel; Guinevere perched on the countertop — Each of Arthur’s brilliant knights complained in turn about Athens, about the stifling heat — About their stifling boredom — About the girls in bars who wouldn’t glance at so much as through them — I squeezed an orange into a glass and a rogue drop pricked at my eye but the juice set off soothing citrus sunbursts on my tongue — The others wrestled, half in jest and half in anger as was their nature, and I imagined beating them all with a chair, as was mine — The rumblings of slow-moving traffic drifted from hot cement to open windows, an itch in the corner of my consciousness — Eventually it was decided that we would join our illustrious king’s father on a quest, visit the obstinate farmer in his village (no: hamlet) an hour from Athens — Tonight was the village panigiri — One last night to drink and dance the kalamatianos in concentric circles with the happy fools, hands sticky from grilled corn and fried dough.

That evening we returned to his ever-loyal truck, the door handles almost hot to the touch after a few minutes of exposure to the soon—setting sun — We chased the sun into the mountains, the off-white blur of civilisation fading fast behind us as we trailed behind his father’s convertible until it peeled off, a farmer to convince — And we continued down the same road, the only road, into the village — The heat had dulled my appetite; I felt expansive, lethargic. By the time we arrived at the festival grounds, I had grown hollow — Only picked at my supper, silence all around, his father unsuccessful in convincing the farmer to concede his land — The village church struck eleven and we all dispersed: father back to Athens, son to the dance floor, pulling her with him, the others to buy beer, gorge themselves, sit at the long table and spill out onto the plastic tablecloth. I wandered from stall to stall, taking offered drinks, drawing bill after bill from my pocket, throwing them like seeds to the wind: here a chicken skewer, here a syrup—soaked sweet — Dazed, I spun and spun and spun.

Alone in the truck bed, desperately thirsty, caramel on my tongue and corn fibres between my teeth — My fingers found the lighter nestled close to my thigh — Hand-engraved, lifted from a gift shop in Niagara Falls on a school trip — Fourteen, he and I had left the others in our cabin to play cards and ventured to the edge of the woods (silently, afraid of the bears we had been warned of but had not yet seen), where we had struggled to light a cigarette in the biting wind—just one for the two of us, stale, transported in a Ziploc bag — My thumb bore a callous for the rest of that trip, but I kept the lighter, displayed it on my nightstand, replaced the flint when it spat weakened sparks — Used it to light foul-smelling cigars, an early graduation gift from his father, before senior year prom — I flicked it on and inspected the engraving, its edges beginning to wear — I held it beneath a crumpled receipt — Watched it flare bright and disappear — And cast in its glow — In those seconds of brilliance — The spare fuel can, army—green and ugly in the corner. I thought of his father standing mute in anger, of that constant disgust passed from father to son. I thought of gratitude and debt and admiration and the frisson of doing something magnificent and terrible and substantive, a quantifiable cause-and-effect. I thought of headlines crawling across television screens and airtankers sweeping above smoking, darkened earth — Future questions: How many stremma burned? Is the blaze contained? Will it threaten Athens? — I picked up the fuel can — My ankle twinged as I leapt from the cargo bed, down to the dirt.

Before my eyes could properly adjust to the darkness I stood, lighter in hand, at the edge of the farmer’s property, past the driveway into which I had seen the cream convertible turn just hours earlier — Futile: that failed negotiation, father and son taciturn at the dinner table — The memory felt false, as though all that was and had ever been real was the present moment; the puddle of gasoline at my feet; what I was on the verge of creating — The lighter jammed, worn flint protesting — I coughed, fuel vapours clinging to my taste buds and nostrils, mixing with the sickly sweet scent of manure hanging in the air — Flicked the lighter again, hot friction against the pad of my thumb — Again — Again — And a spark. I leaned forward, flame readied, but the image of my exposed face blistered and raw flashed through my mind and I stepped a few paces backwards — Raised my arm — Launched the lighter into the waiting underbrush — The flame caught instantly — For a moment it seemed to die, slowing — But what had been a thin crescent-flare tripled, and the fire turned in on itself, roiling, flaring — Within seconds: Inferno — I stood above the flames and watched them, the silent keeper of that incandescent hair combed across the field by the breeze’s sleeping breath, soft in the nighttime, just enough — To spur them on — Leaping from dried blade of grass to desiccated thistle to tree branch to the hardy leaves — Climbing trunks, greedy for their fruit, licking, a million tongues turning orange husks and wasp-bodies to ash — The blaze stretched slender fingers one, two, three metres high — I turned and ran.

Twenty minutes later, side aching, chest heaving, I slipped back into the Bacchanalia, tripping over unsupervised children and plastic chair legs — Danced in a circle, step-step-kick, hand in sweaty hand, breathless — I lost my mind in the spinning mass of arms and legs and hot breath, eyes closed, until I felt it began to slow, faltering — The music stuttered — I stopped — Opened my eyes — In the distance, spotlighted by the gaudy lights strung around town: a plume of smoke, drifting slowly — The softest gasp from the woman next to me, with whom I had been circling, hand in hand, ten seconds before — Then a shout, guttural, panicked, a father’s fear: Fire! Picked up by the crowd, echoed in whispers and shrieks—What’s going on? Oh my god, where are the kids? — Let’s get to the car — No, too dangerous, we don’t know where the danger is — Maybe it’s nothing? — Call the police! — Moments later, in the near distance: sirens.

I staggered and sped along with the crowd at an opportunistic policeman’s behest (surely imagining himself a Greek Paul Revere, the first to sound the alarm, saviour of the village, he hoisted himself onto the stage and, prying the microphone from the speechless singer’s grip, ordered us out into the street) — Families clustered on the main road, people in nightclothes standing confused on stoeps, roused from sleep by the mob’s hysterics — Drivers honked, swore, gestured at the flock of people like they would at goats blocking mountain roads — I stood solitary, face tingling, flushed with the realness of it all — I wanted to die — Nothing would ever feel better, nothing could ever be worse — Unmoving, I watched an hour pass — Until we were herded down the street, shuffling in lockstep, into the lobby of the village’s only hotel.

No service, the police occupied with wailing children and fretful mothers, the hotel phone engaged, still engaged — To my halting query an old woman replied that the other evacuation spot was the school gymnasium, a newly inaugurated basketball court a number of kilometres away — The others, then, would be sitting safe (but complaining still, picking at the laminated slats of hardwood, testing stiff shoulders after naps against the padded walls or across the free throw line) — She would sleep on his shoulder, I expected. I imagined his father might have driven back up from the city, could be navigating his polished convertible through the narrow, murky village roads, searching for me — Nothing to do but wait, blood still humming with the joy of devastation, cross-legged on the carpeted floor.

The reception hall had a print of a waterfall painting on the wall — Far from Attica, a Hudson River School rip-off from some museum gift shop — Little glossy slice of American wilderness for the intrepid pioneers venturing twenty miles from the city into the wilderness with its coarse inhabitants and their Rural Dionysia — But I remembered — Fuck — I remembered! — The lighter I had cast onto the grass, into which he and I had carved our initials, the brass, unburning lighter, a metal betrayal calling my name, gleaming in the ashes, waiting for a firefighter, policeman, anyone to pick it up — I hastened, trembling, down the hallways, past the kitchen’s double-doors, past the toilets, past ice machines and supply closets, around corner after corner until an exit appeared, cross-hatched window glowing with harsh early-morning light. The soot-saturated air stifled my desperate gasps as I ran to the festival grounds, past discarded purses and half-drunk beer cans stewing in the sun, behind the stage to the parking lot — I pressed onto his keys, the only thing left in my pocket, and heard, from across the lot, the truck’s inviting yelp.

The country roads were transformed by the daylight: illuminated, they were larger, wider, more accommodating than their claustrophobic nighttime alter egos. Breaths coming sharply, haltingly, I accelerated through turns, tyres wailing — I counted my heartbeats — Barely three hundred and I had arrived — If the others had been there, he would have quipped the scene of the crime and they would’ve all coughed half-witted laughs from deep in their throats — The ground smoldered underfoot as I stepped from the car, crouching, blood thrumming in my temples — The fields were deserted as far as I could see; the fire had abandoned this land, moved to neighbouring nourishment; the firefighters’ sirens echoed faintly, occupied elsewhere — I straightened — The only sounds the truck engine’s growl and the gentle crackling of small unattended flames, dying fast — I scanned the blackened earth, pacing, imagining men in turnout gear pulling the lighter intact from the dirt, tracing my initials with thick gloves — No! — There, half-buried, a brass blur — I kneeled, knees tender against the too-warm ground — I lifted the mangled, flame-disfigured lighter from its earthen cradle — But it stung, still hot, eating away at my skin — I yelped, dropped it back to the earth, revealing its other side, engraving melted away — Frenzied, I scooped handful after handful of hot loam, piling it above the lighter until the metallic gleam disappeared from my mind’s eye — I stood, hands blackened, right fingertips bloodied, shoulders beginning to burn — Desolate — I turned in a circle, surveying the ravaged land — Alone — But eastwards, concealed among twisted husks of seared trees: a ruin, sibling to the little house in the South — One room, singed walls — I approached, pressed on a tree trunk — Watched it crumble beneath my touch —

The shack’s roof tin roof was heat-warped, twisting down between the still-intact walls — I drew closer; neared the sole window-frame, splintered glass scattered beneath the sill — There — Framed by the soot-stained opening — Two figures, girl and boy, slumped by the doorway — No, no — He was closer, collapsed, arm stretched towards the doorway, scar stretched silver across blue-grey skin, fingers burnt raw like mine — No — And her, arm across his back, shirt undone, fingers curled stiff, hair swept across still-open eyes — I stumbled backwards, fell into waiting shards of window-pane but could not feel the fragments biting into my palms — I imagined them walking hand in hand from the festival, crossing the fields as I walked a parallel path down empty roads — Saw them dizzy with smoke — Saw him reach for the doorknob and recoil, screaming, flame-bathed handle too painful to grasp — Saw him kick at the door once, powerful, twice, weak, stagger backwards into her outstretched arm, pull her forwards — A desperate wheeze — A final swoon in a smoke-clogged room.

I found myself back in the driver seat of his truck, holding his keys in my bleeding hand, shivering, choking in the heat — Alone — No policemen, no firemen, no farmer, empty road, empty car — I drove — Screeched to a halt, vomited yellow kernels and cloying sweetness, heaving out of the window — Back to the hotel, through the back, into the bathroom, scrubbing my blistering hands, skin peeling, retching into the sink, hot bile stinging my lips, holding my face under the tap until I felt human again — Into the reception, unnoticed, where I held the pathetic waterfall print in my gaze until evening, the hours eroding like the dead olive tree in my hands.

The others, I learned in time, had indeed sheltered in the gymnasium — Arguing, surely — Thinking I was with him, or us with her, all safe, surely. His father had stayed in Athens, worked into the late hours of the night, television off, oblivious — What a surprise the following morning, to find his world consumed by the flames — His business days came to an end after that — The farmer sold his land, but no father could raise a resort over his son’s dying-place — So my father, the vulture, bought it — Now I drive, alone, thirty-one, one too many in the car going north to survey the construction — The development, my father’s legacy passed on to me—my legacy built on flint and spare fuel—will make me, mark me, secure me — My children will go to Philips Exeter Academy; my son will trace my steps to Cornell — We will not vacation in Greece; I will say work and home should not mix — The apartment will gather dust but the housekeeper will sweep the floor, faithful, until it shines, no shoes to smudge it — His pickup truck still sits rusting in my apartment garage — A parting gift — A reminder — (No one noticed my heat-ravaged hand until years later — When my wife, caressing my palm with her thumb, wondered quietly at the baby-smooth flesh.)